Today marks the 29th installment in a series of articles by HumanProgress.org titled, Heroes of Progress. This bi-weekly column provides a short introduction to heroes who have made an extraordinary contribution to the well-being of humanity. You can find the 28th part of this series here.

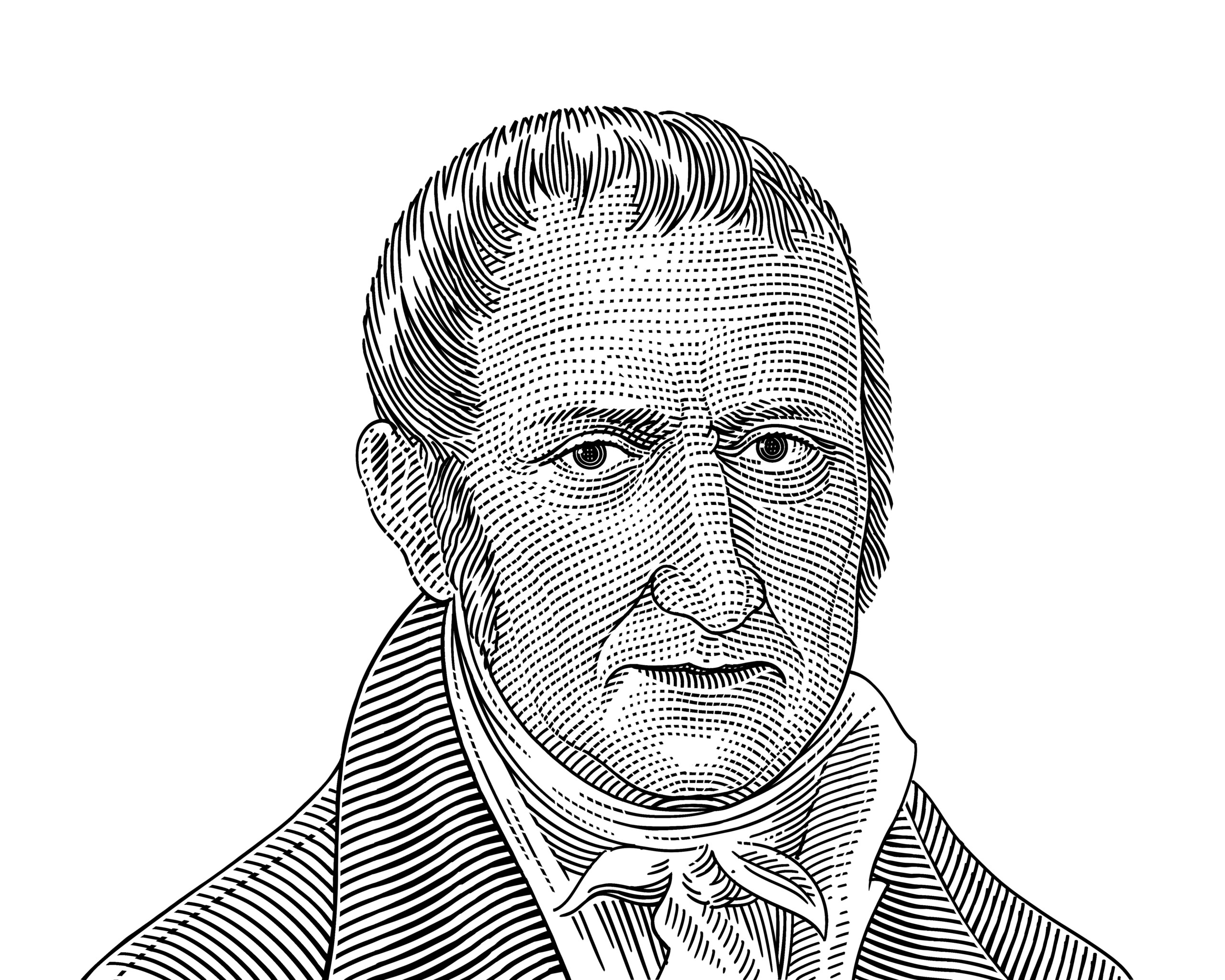

The week, our hero is the Italian physicist Alessandro Volta, who invented the world’s first electric battery. His “Voltaic pile” provided the first source of continuous electric current the world had ever seen. Through his discovery, Volta debunked the prevalent theory at the time that electricity was generated solely by living beings. Volta’s invention laid the groundwork for modern batteries. His work also helped to create the field of electrochemistry and electromagnetism.

Alessandro Giuseppe Antonio Anastasio Volta was born on February 18, 1745 in Como, a town in present-day northern Italy. Volta’s family was noble and wealthy. As a child, he attended a Jesuit boarding school, where his teachers tried to persuade him to enter the priesthood. Volta knew that his real passion lay in physics and, at the age of 16, he dropped out of school. Despite not receiving any further formal training, Volta began to exchange letters with leading physicists of the day by the time he was 18. Two years later, Volta was already conducting experiments in a physics lab built by his wealthy friend, Giulio Cesare.

By 1774, Volta was teaching experimental physics in Como’s public grammar school. At this point, Volta’s work primarily focused on the chemistry of gases. In 1778, after reading a paper written by Benjamin Franklin on the topic of “flammable air,” Volta became the first person to discover and then isolate the gas methane. Volta found that a methane-air mixture could be exploded with an electric spark when in a closed container. This type of electrically induced chemical reaction would later become the basis of the internal combustion engine.

In 1779, Volta was appointed professor of experimental physics at the University of Pavia, a position he would maintain for almost 40 years. Volta spent his first years in Pavia studying what we now call “electrical capacitance.” He found that electrical potential in a capacitor (the capacitor is a component which has the ability or “capacity” to store energy in the form of an electrical charge) is directly proportional to its electric charge. Today this phenomenon is called Volta’s Law of Capacitance.

In 1791, Volta’s friend and fellow physicist Luigi Galvani found that he could get a frog’s leg that was mounted on iron or brass hooks to twitch when the leg was touched with a probe made from another metal. Galvani interpreted his discovery as a new form of electricity that can be found in living tissue and named it “animal electricity.” Volta disagreed with Galvani’s findings. He hypothesized that the frog merely conducted the electrical current which flowed between the iron or brass hook and the other metal that was being used as a probe. Volta called this type of electricity “metallic electricity.”

Volta then began experimenting to see if he could produce an electrical current with metals alone. As instruments at the time were unable to detect weak electrical currents, Volta tested the flow of electricity between different metals by placing them on his tongue. Sure enough, Volta found the saliva in his mouth, like the frogs’ tissue in Galvani’s experiments, conducted electricity – causing a bitter sensation.

In order to show conclusively that an electric current did not require an animal tissue, Volta created a stack of alternating zinc and silver discs, which were separated by brine-soaked cloth. Volta found that when a wire was connected to both ends of the pile, a steady current flowed between the layers. This invention, which came to be known as the voltaic pile, was really an early form of today’s electric battery. After numerous experiments, Volta also found that the amount of current produced could be increased or decreased by using different metals or adding and taking away disks from the pile.

Volta first reported his electric pile experiment in a letter dated March 20, 1800. It was addressed to Joseph Banks, the president of the Royal Society of London. Soon after, Volta travelled to Paris to demonstrate his invention, which he initially called an “artificial electric organ.”

Volta’s battery was a huge success. Not only did it destroy the scientific consensus around “animal electricity,” but scientists quickly recognized Volta’s “artificial electric organ” as an extremely useful device. Within six weeks of Volta announcement, English scientists William Nicholson and Anthony Carlisle used their own voltaic pile to decompose water into hydrogen and oxygen, which led to the discovery of electrolysis or “a technique that uses a direct electric current to drive an otherwise non-spontaneous chemical reaction” and thus created the field of electrochemistry. Similarly, in the 1830s, another English scientist, Michael Faraday, used the voltaic pile in his ground breaking studies of electromagnetism.

Napoleon Bonaparte was so impressed with Volta’s work that he made Volta a count in 1801 and senator of the kingdom of Lombardy. In 1809, Volta also became an associated member of the Royal Institute of the Netherlands.

Volta retired in 1819, aged 74. He moved to his estate in Camnago, which was later renamed “Camnago Volta” in his honor. On March 5, 1827, Volta died at the age of 82. Since his death, Volta has appeared on stamps and currencies. His name was immortalized when the measure of electric potential, or “volt,” was named after him in 1881.

Volta’s invention of the early battery not only helped to lay the groundwork for the creation of several scientific fields, but the battery has become a staple of the modern world. Without Volta’s work, many of our modern technologies would not exist. For that reason, Alessandro Volta is our 29th Hero of Progress.